3 AI-Ready Data in Arctic Research

Goal

This session dives into the concept of ‘AI-ready data’ in Arctic science and geoscience, highlighting the importance of suitable data for AI applications. Participants will learn about creating and managing metadata and organizing data repositories. We’ll discuss best practices for data preparation and structuring for AI processing. By the end, participants will clearly understand AI-ready data characteristics and the steps to transform raw data for AI applications.

3.1 Are we ready for AI?

Data that are accessible, preferably open, and well-documented, making them easily interpretable and machine-readable to simplify reuse.

This is really a variant on Analysis Ready Data (ARD), or, more recently, “Analysis Ready, Cloud Optimized (ARCO)” data.

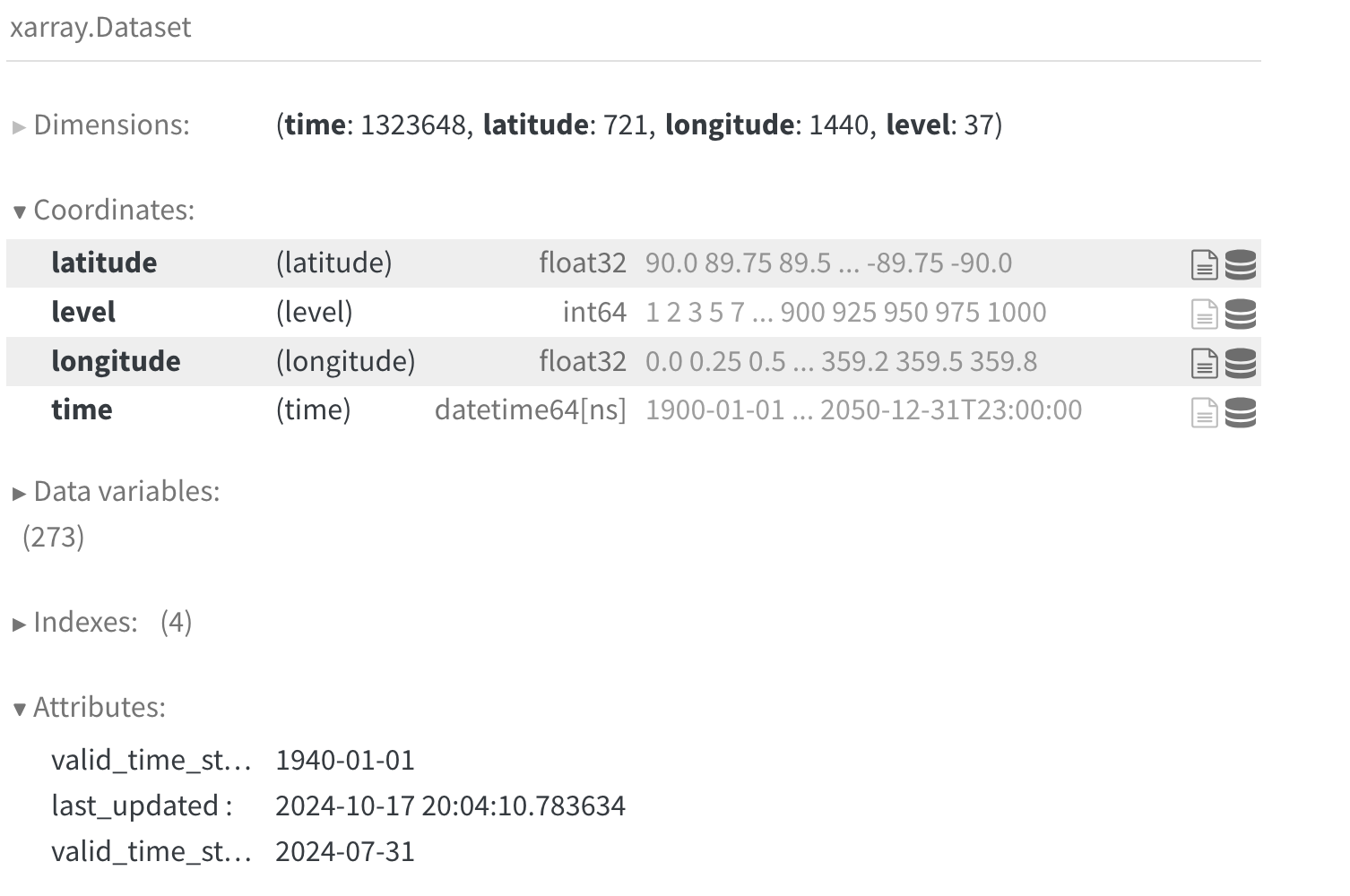

Working with xarray and zarr, one can access many multi-petabyte earth systems datasets like CMIP6 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6) and ERA5 (Earth Re). For an overview of Zarr, see the Arctic Data Center Scalable Computing course chapter on Zarr.

Take, for example, the ERA5 reanalysis dataset [2], which is normally downloadable in bulk from the Copernicus Data Service. ARCO-ERA5 is an Analysis Ready, Cloud Optimized variant of ERA5 which has been reprocessed into a consistent 0.25° global grid, and chunked and saved in Zarr format with extensive metadata such that spatial and temporal subsets are easily extracted. Hosted on the Google Cloud Storage service in a public bucket (gcp-public-data-arco-era5), anyone can easily access slices of this massive multi-petabyte dataset from anywhere on the Internet, and can be doing analysis in seconds. Let’s take a quick peek at this massive dataset:

import xarray

ds = xarray.open_zarr(

'gs://gcp-public-data-arco-era5/ar/full_37-1h-0p25deg-chunk-1.zarr-v3',

chunks=None,

storage_options=dict(token='anon')

)

dsWith one line of code, we accessed 273 climate variables (e.g., 2m_temperature, evaporation, forecast_albedo) spanning 8 decades at hourly time scales. And while this dataset is massive, we can explore it from the comfort of our laptop (not all at once, for which we would need a bigger machine!).

So, there’s nothing really special about AI-Ready data, in that a lot of the core requirements for Analysis Ready Data are exactly what are needed for AI modeling as well. Labeling is probably the main difference. Neverthless, many groups have gotten motivated by the promise of AI, and particularly machine learning, across disciplines. For example, the federal government has been ramping up readiness for AI across many agencies. In 2019, the White House Office of Science Technology and Policy (OSTP) started an AI-Readiness matrix, which was followed shortly by the National AI Initiative Act in 2020 [3].

For example, management agencies have started entire new programs to prepare data and staff for the introduction of AI and machine learning into their processes. One such program with a focus on AI-Ready data is NOAA’s Center for Artificial Intelligence (NCAI).

In beginning to define AI-Ready data for NOAA, Christensen et al. 2020 defined several axes for evaluation, including data quality, data acess, and data documentation. We’ll be dinving into many of these today and over the course of the week.

- Completeness

- Consistency

- Lack of bias

- Timeliness

- Provenance and Integrity

- Formats

- Delivery options

- Usage rights

- Security / privacy

- Dataset Metadata

- Data dictionary

- Identifier

3.2 Open Data Foundations

Preservation and open data access are the foundation of Analysis-Ready and AI-ready data. While all modeling and analysis requires access to data, the ability for AI to encompass massive swaths of information and combine disparate data streams makes open data incredibly valuable. And while the open data movement has seen massive growth and adoption, it’s an unfortunate fact that most research data collected today are still not published and accessible, and challenges to the realization of open data outlined by Reichman et al. (2011) are still prominent today [4].

3.3 Arctic Data Center

Nevertheless, progress has been made. The National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs Data, Code, and Sample Management Policy (DCL 22-106) embraces the need to preserve, document, and share the data and results from NSF-funded research, and since 2016 has funded the Arctic Data Center to provide services supporting reseach community data needs. The center provides data submission guidelines and data curation support to create well-documented, understandable, and reusable data from the myriad projects funded by NSF and globally each year. In short, the Arctic Data Center provides a long-term home for over 7000 open, Arctic datasets that are AI-Ready. Researchers increasingly deposit large datasets from remote sensing campaigns using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), field expeditions, and observing networks, all of which are prime content for AI.

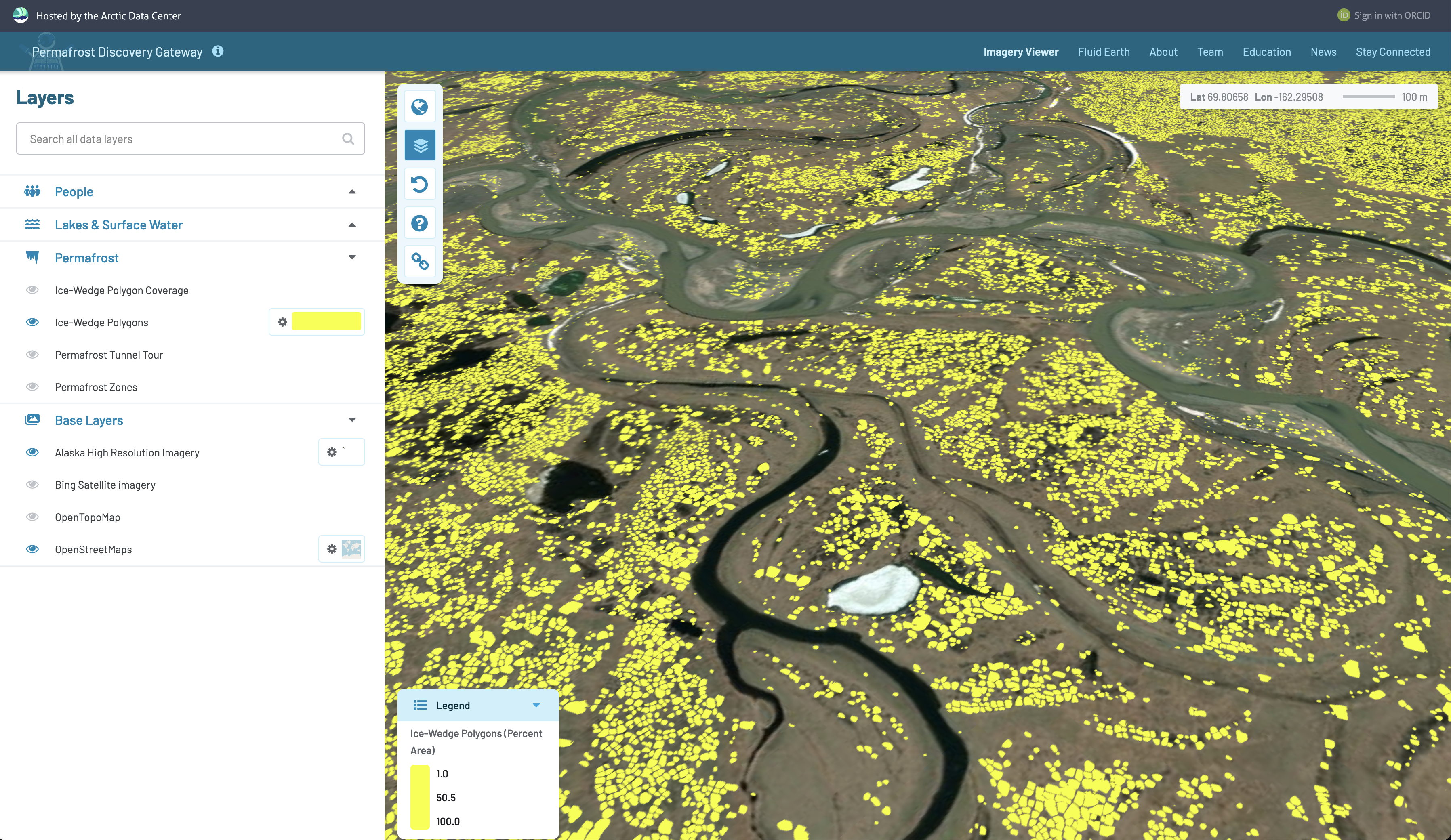

In addition to raw observational data and remote sensing imagery, the ADC also stores and distributes model output, labeled training data, and other derived data products. A recent example comes from the Permafrost Discovery Gateway project, in which Neitze et al. used machine learning on multispectral PlanetScope imagery to extract high-resolution geospatial footprints for retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS) and active layer detachment (ALD) slides across the circum-Arctic permafrost region [5]. In addition, the dataset includes human-generated training labels, processing code, and model checkpoints – just what is needed for further advances in this critical field of climate research.

While this and other valuable data for cross-cutting analysis are available from the Arctic Data Center, there are many other repositories that hold relevant data as well. Regardless of which repository a researher has chosen to share their data, the important thing to remember is to do so – data on your laptop or a University web server are rarely accessible and ready for reuse.

3.4 DataONE

DataONE is a network designed to connect over 60 global data repositories (and growing) to improve the discoverability and accessiblilty of data from across the world. DataONE provides global data search and discovery by harmonizing myriad metadata standards used across the world, and providing an interoperability API across repositories to make datasets findable and programatically accessible regardless of where they live.

For example, a query across DataONE in 2024 revealed over 4500 datasets held by 16 different repositories, most of which are not specifically tied to Greenland research, per se.

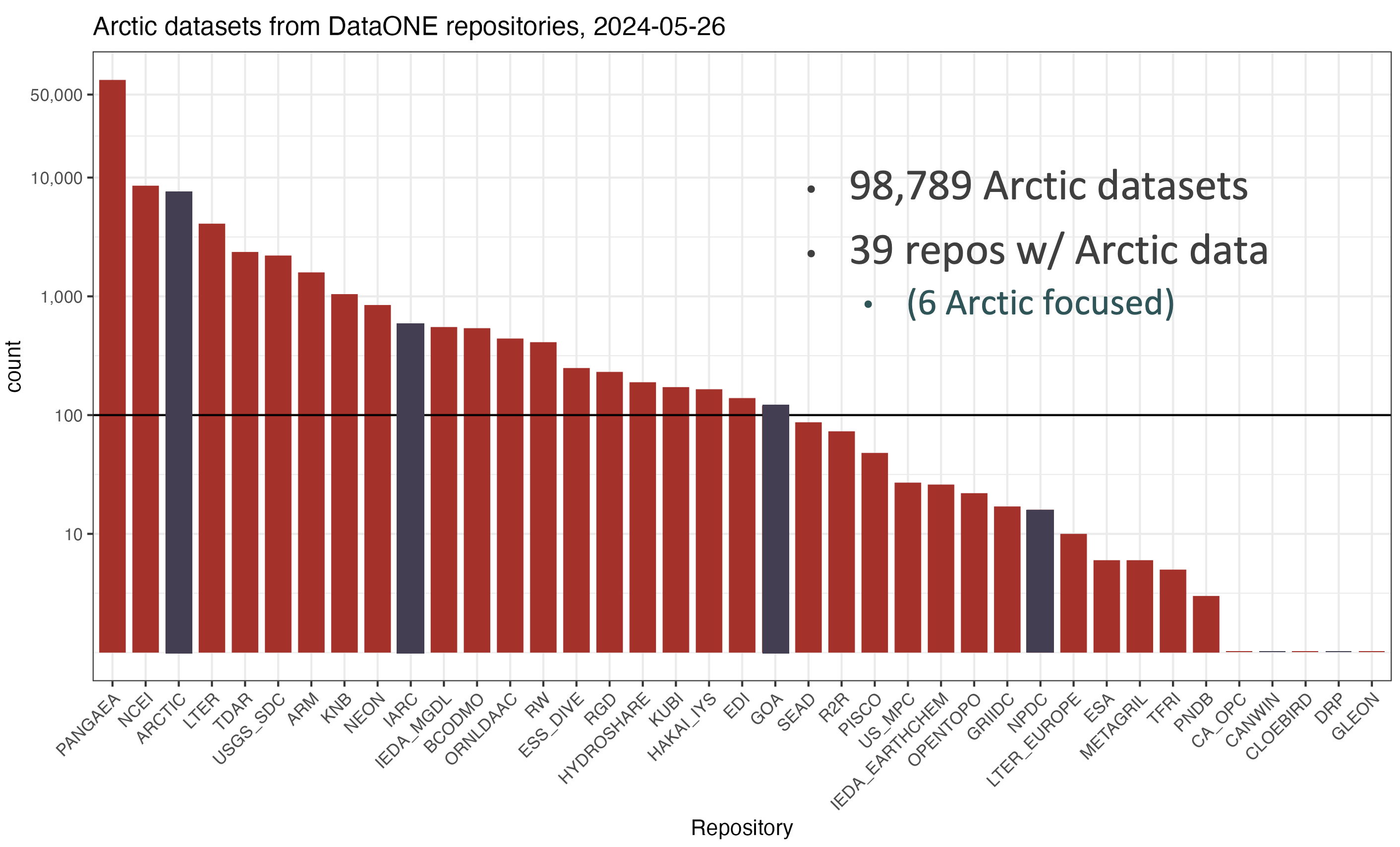

Looking across the whole of the Arctic, we found over 98,000 datasets from 39 data repositories. It is notable that only 6 of those repositories are focused on Arctic research (like the Arctic Data Center), while the rest are either general repositories or discipline specific repositories. For example, Pangaea as a generalist repository has the most datasets with over 10,000, but there are also significant and important data sets on archeology (TDAR), hydrology (HydroShare) and geochemistry (EarthChem).

3.5 Metadata harmonization

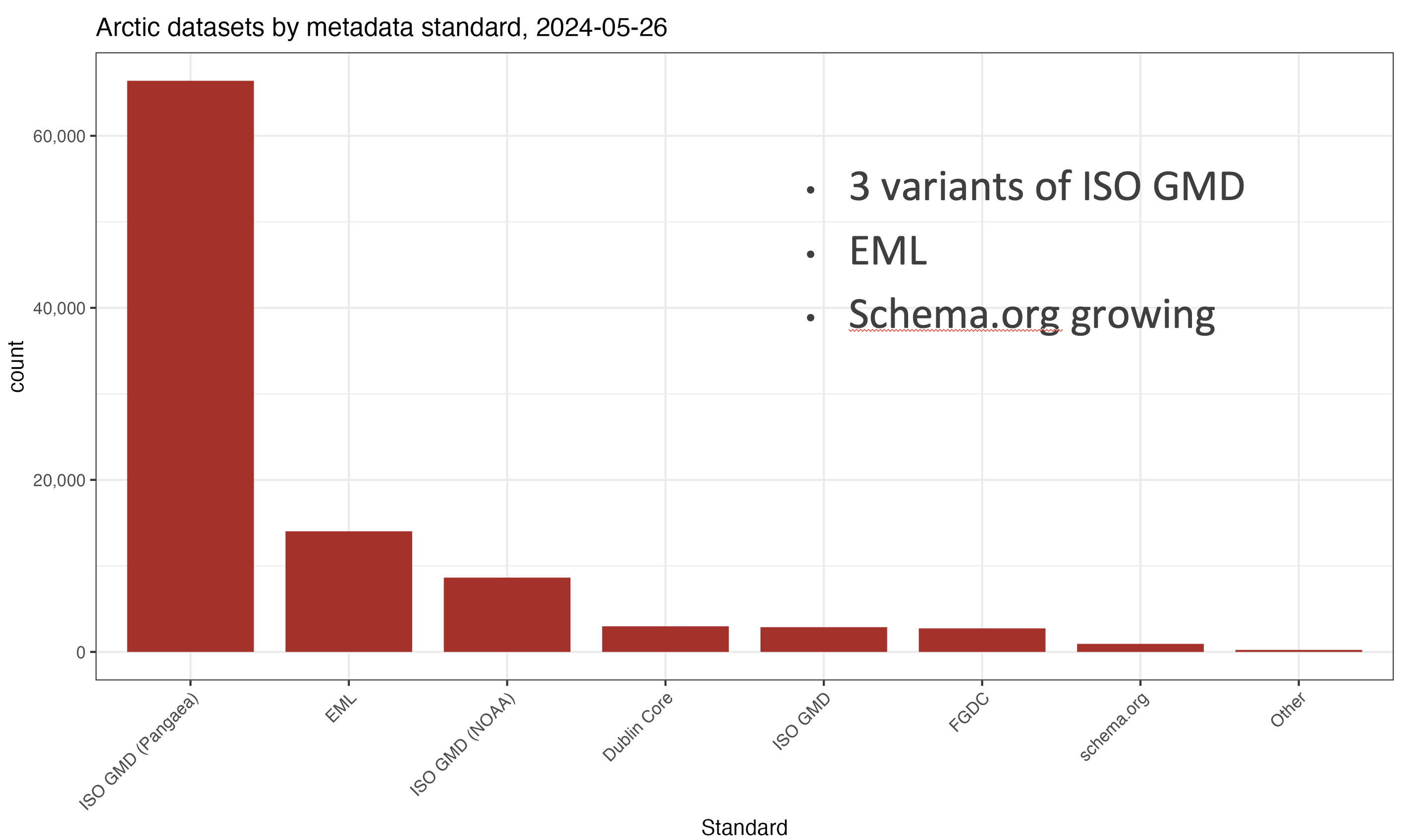

One of the main roles of DataONE is to promote interoperability and improve the quality and discoverability of global data holdings – all of direct benefit to AI Ready data. DataONE promotes the use of detailed, discipline-specific metadata standards that enable researchers to comprehensively document the structure, contents, context, and protocols used when collecting data. For example, a good metadata record records not only the bibliographic information about the Dataset creators, but also documents the spatial and temporal extent of the data, the methods used to collect it, the types of measured properties that were observed or modeled, and other details that are fundamental to the proper interpretation and reuse of the data. Different disciplines focus on different standards: in ecology and environmental science, where biological metadata on taxonomy are important, the Ecological Metadata Language (EML) is used extensively, whereas in geospatial science where time and space are critical, the emphasis is on the ISO 19115 family of metadata standards. Overall, DataONE supports more than a dozen metadata variants, and can be extended to support more. Across the Arctic, we find datasets that use many different metadata approaches.

DataONE harmonizes these standards by cross-walking them conceptually and making the data available for search through an integrated discovery portal and API. And DataONE promotes semantic labeling of the data as well, particularly for measurement types (e.g., fork length for fish length meeasurements) and dataset classification [6]. These annotations are indexed against controlled, ontologically-precise term labels that are stored in queryable systems. For example, the Ecosystem Ontology (ECSO, the Environment Ontology (ENVO), and many others contain precisely defined terms that are useful for precise dataset labeling to differentiate subtly different terms and concepts.

3.6 Croissant metadata for machine learning

While domain-specific metadata dialects continue to proliferate, an increasing number of data repositories support schema.org as a lingua franca to describe datasets on the web for discoverability. The Science on Schema.org (SOSO) project provides interoperability guidelines for using schema.org metadata in dataset landing pages, and DataONE supports search across repositories that produce schema.org. That said, the dialect is fairly lightweight, somewhat lossely defined, and therefore permits some ambiguity in usage. But it has the major advantage that, as a graph-based metadata dialect, it can be easily extended to support new terms and use cases.

The Croissant specification [8] extends schema.org with more precise and structured metadata to enable machine-interpretation and use of datasets across multiple tools. While the vocabulary is not as rich as, for example, the ISO 19115 metadata for geospatial metadata, it does provide a more strict structural definition of data types and contents that plain schema.org. A quote from the specification illustrates its intended scope [8]:

The Croissant metadata format simplifies how data is used by ML models. It provides a vocabulary for dataset attributes, streamlining how data is loaded across ML frameworks such as PyTorch, TensorFlow or JAX. In doing so, Croissant enables the interchange of datasets between ML frameworks and beyond, tackling a variety of discoverability, portability, reproducibility, and responsible AI (RAI) challenges.

Croissant has also explicitly defined metadata to meet the needs of machine-learning tools and algorithms. For example, Crosissant supports the definition of categorical values, data splits for training, testing, and prediction, labels/annotations, specification of bounding boxes and segmentation masks.

Label Data. As an example, Crioissant has specific metadata fields designed to capture which fields with the data contain critical label data, which are used by supervised learning workflows. The Croissant metadata class cr:Label can be used in a RecordSet to indicate that a specific field contians labels that apply to the that record.

{

"@type": "cr:RecordSet",

"@id": "images",

"field": [

{

"@type": "cr:Field",

"@id": "images/image"

},

{

"@type": "cr:Field",

"@id": "images/label",

"dataType": ["sc:Text", "cr:Label"]

}

]

}The intention is that multiple tools, all supporting the Crosissant metadata model, will be able to exchange ML-related data seamlessly. A number of ML tools support Croissant out-of-the-box, but only a tiny fraction of the datasets available today use this nascent vocabulary. In addition, it lacks the sophistication of Analysis Ready, Cloud Optimized (ARCO) data standards like Zarr that permit seamless access to massive data with minimal overhead. But it has a lot of promise for streamlining AI-Ready data, and can be used on top of exiting standards like Zarr.

3.7 Data Quality

One of the primary determinants of AI-Ready data is whether the data are of sufficient quality for the intended purpose. While the quality of a dataset may have been high for the iniital hypothesis for which it was generated, it might be quite low (e.g., due to biased or selective sampling) at the scales at which machine learning might operate. Consequently, it is fundamentally important to assess the quality of datasets during the planning and execution of an AI project. Questions such as the following would be of prime interest:

- Does the dataset represent the complete population of interest?

- Does training data reflect an unbiased sample of that population?

- Are the data well-documented, enabling methodological interpretation?

- Did data collection procedures follow standards for responsible AI and ethical reseatch practices?

- Are the data Tidy (normalized) and structured (see Tidy Data lesson)?

- Are geospatial data accessibly structured, with sufficient metadata (e.g., about the Coordinate Reference System)?

- …

Many of these issues are encompassed by the FAIR Principles, which are intended to ensure that published data are Finadable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [9], [10]. While there are a huge variety of methods to assess data quality in use across disciplines, some groups have started to harmonize rubrics for data quality and how to represent data quality results in metadata records (see [11]).

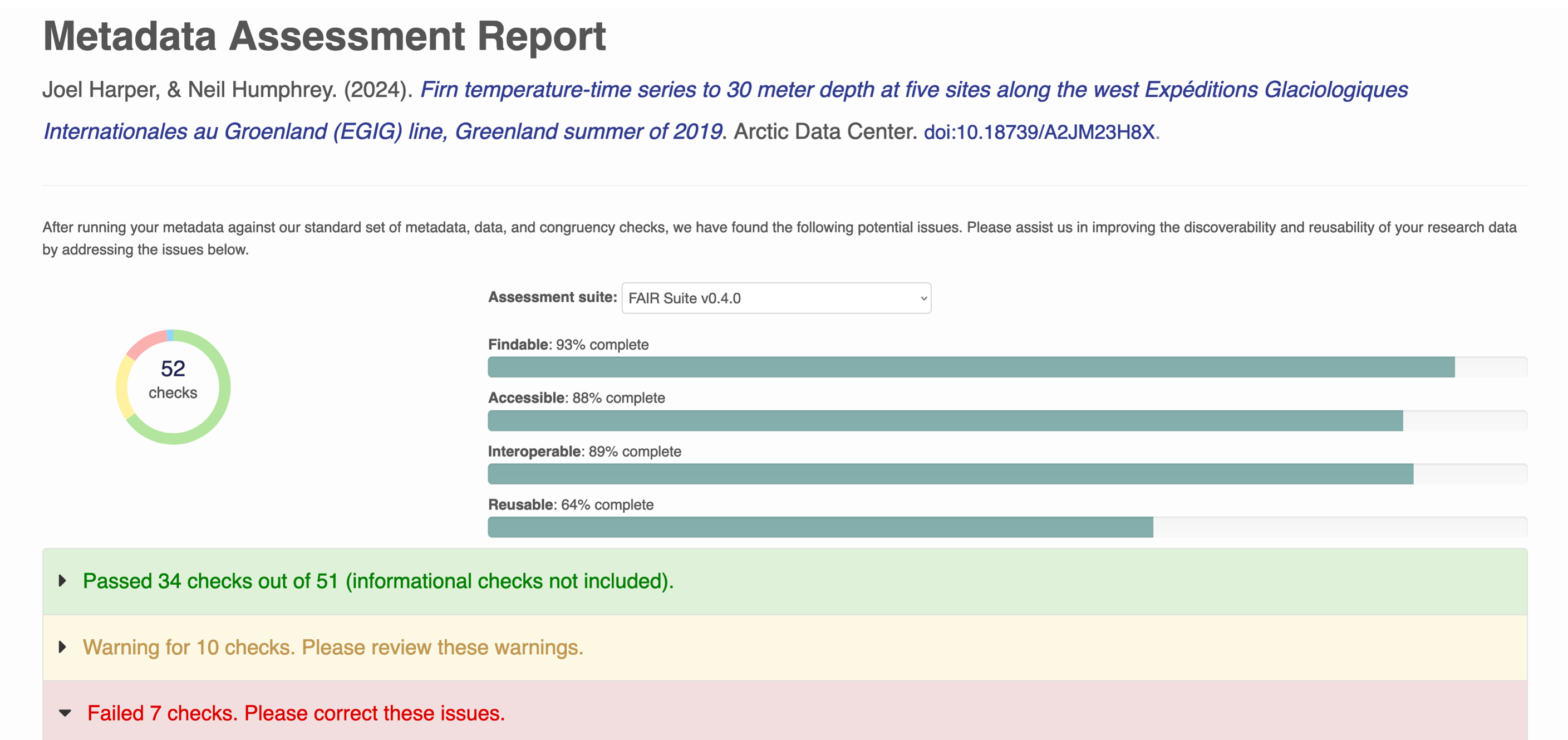

DataONE is one such group that has operationalized FAIR Assessment [11]. Within the DataONE network, all compatible datasets are evaluated using an automated FAIR rubric which rates the dataset on 52 FAIR checks [12], [13]. Each of these checks is atomic, and looks at a small facet of the dataset quality, but combined they give a powerful assessment of dataset readiness for various analytical purposes. And these suites of checks are extensible, so different groups can create suites of automated quality assessment checks that match their needs and recommendations as a community.

We see a marked improvement in dataset quality across the FAIR axes as datasets go through our curation process at the Arctic Data Center.

The Arctic Data Center team is currently working to extend this quality assessment suite to deeper data quality checks. Most of the current checks are based on metadata, mainly because these are accessible through the centralized DataONE network, whereas data are distributed throughout the network, and are much larger. The ADC data quality suite will assess generic quality checks and domain-specific quality checks to produce both dataset-level and project-level quality reports. Some of the key types of checks that are posisble with the system include:

| Generic Checks | Domain/Discipline Checks |

|---|---|

| Domain and range values | Tree diameters don’t get smaller |

| Data type conformance | Unit and measurement semantics |

| Data model normal | Species taxonomy consistent |

| Checksum matches metadata | Outlier flagging |

| Malware scans | Allometric relations among variables |

| Characters match encoding | Calibration and Validation conformance |

| Primary keys unique | Temporal autocorrelation |

| Foreign keys valid | Data / model agreement |

3.8 ESIP AI-Readiness Checklist

To round out our survey of AI-Readiness in data, let’s look at the AI-Readiness Checklist that has been developed by an inter-agency collaboration at the Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP) [14]. This checklist was designed as a way to evaluate the readiness of a data product for use in specific AI workflows, but it is general enough to apply to a wide variety of datasets. In general, the checklist asks questions about four major areas of readiness:

- Data Preparation

- Data Quality

- Data Documentation

- Data Access

The challenge with this checklist and others is that readiness is truly in the eye of the beholder. Each project has unique data needs, and what is a fine dataset for one analytical purpose (e.g., a regional model) may be entirely inadequate for another (e.g., a pan-Arctic model).

There are a huge variety of datasets available from DataONE and the Arctic Data Center, and many other repositories. In this exercise we will do a quick assessment of AI Readiness for the ice wedge polygon permafrost dataset from the Permafrost Discovery Gateway project [[5]], using the ESIP AI-Readiness Checklist.

Link to dataset: - doi:10.18739/A2KW57K57 - Visualize Permafrost Ice Wedge Polygon data on PDG:

We’re going to break into groups, and each group will work on a portion of the evaluation for the dataset. The groups are:

- Group A (Preparation)

- Group B (Data Quality)

- Group C (Data Documentation)

- Group D (Data Access)

Instructions: - Make a copy of the AI-Readiness Checklist spreadsheet - Split into 4 groups and try to quickly answer the questions (we won’t really have time, so don’t get too bogged down)

Questions to consider as you are doing the assessment: - How much time would it take for you to do a true assessment? - How useful would this assessment be to you if it were available for most datasets? - Is there a correct answer to the checklist questions?

![Mahecha et al. 2020. [1] Visualization of the implemented Earth system data cube. The figure shows from the top left to bottom right the variables sensible heat (H), latent heat (LE), gross primary production (GPP), surface moisture (SM), land surface temperature (LST), air temperature (Tair), cloudiness (C), precipitation (P), and water vapour (V). The resolution in space is 0.25° and 8 d in time, and we are inspecting the time from May 2008 to May 2010; the spatial range is from 15° S to 60° N, and 10° E to 65° W.](../images/ai-ready/mahecha_data_cube.png)

![A sub-Arctic salmon-related dataset [7], showing annotations for each of the measured variables in the dataset. Each annotation is to a precisely defined concept or term from a controlled vocabulary, allowing subtle differences in methodology to be distinguished, which helps with both data discovery and proper reuse. The underlying metadata model is machine-readable, allowing search systems, and amchine learning harvesters to make use of this structured label data.](../images/ai-ready/dataone-annotation-salmon.png)

![Common ML data providers like Hugging Face and Kaggle could use Croissant to produce ML-optimized datasets, which in turn can be seamlessly loaded and used with compatible ML libraries such as TensorFlow and PyTorch. Image credit: [8]](../images/ai-ready/criossant-cross-product.png)